Madeira

Served as aperitif or more often after dinner, the wines of Madeira DOC are renowned for their depth of acidity, concentration, and taste of age. Through twin processes of fortification and exposure to heat via maturation in estufagem (tank) and/or canteiro (exposed barrels)—by which it suffers evaporation, concentration and controlled oxidation—a singular and astonishing wine emerges, one that stands in stark contrast to modern winemaking and yet is as diverse in expression, and among a rare breed of wines that are stable after opening. Only eight producers of this wine remain.

Madeira: The Island

Archipelago, actually. Autonomous region of Portugal—founded in 1419—sitting 550 miles off the coast of western Morocco. Volcanic in origin; sub-tropical in climate.

A Special History in America

Loved by our Founding Fathers, especially Ben Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Madeira was in fact America’s most popular wine for more than 200 years, from 1640-1850.

Topography & Terroir

Madeira is a small island, 36 miles east to west; 14 miles north to south, dominated by its spine of jagged mountain peaks and steep coastal cliffs wrought by volcanic activity. Despite its diminutive size, it has an extraordinarily diverse climate, with verdant flora and fertile soils and a welter of individual microclimates.

Viticulture: Tiny Plots

There are a mere 476-hectares (1176 acres), making it one of the smaller vineyards for appellation wine in the world. (To put this into perspective, the total viticultural area of Madeira is just .05% that of Bordeaux.) Island viticulture remains primitive. With some 1500-1700 growers on the island, the average vineyard is less than 1⁄2 an acre situated on a homeowner’s property. Most of the vineyard and harvest work is still carried out by families and neighbors. These plots tend to be less-fertile gravelly soils which over centuries islanders have banked up to form small stone-wall terraces, on which the vines are trained to low pergolas raised 4-6 feet off the ground, under which other crops are often grown simultaneously.

Vinification

Upon arrival, grapes are tested for sugar—9° Baumé, equivalent to 9% abv, is the legal minimum; most fall between 9-11° Baumé. Grapes are destalked, crushed and at some juncture, depending on the grapes and practices of the producer, pressed. In practice, some fermentation on the skins (maceration) is now general, in order to extract as much color as possible from the skins. Vinification typically takes place in steel tanks with native yeasts. Fermentation is arrested via fortification when the sugar level arrives at the natural sweetness appropriate to the type of wine being produced. Thus, for a sweet wine, fermentation can last between 8-24 hours; whereas for a dry wine, 5-6 days. Fortification is about process, not shelf life. The principle behind this is two-fold: the addition precludes continued fermentation (preserving sweetness depending on when it is added) and increases the wine’s production stability due not only to the inhibition of fermenting yeasts but also other microbial activity (spoilage yeasts, bacteria).

Belem’s

Portugal ➜ Madeira DOC 17.0% ABV

Saveiro

Portugal ➜ Madeira DOC 19.0-20.0% ABV

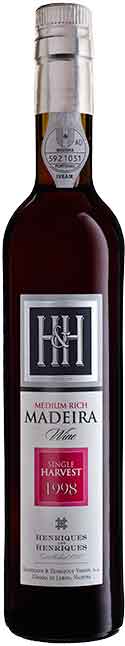

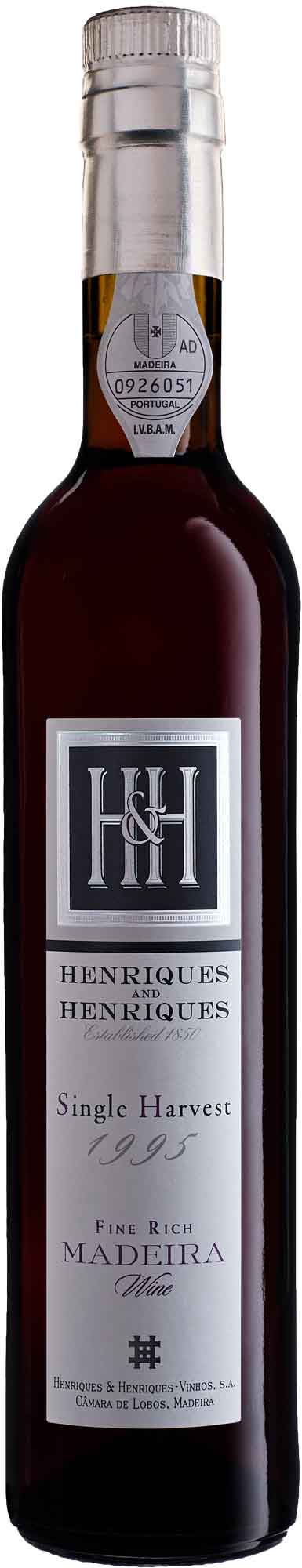

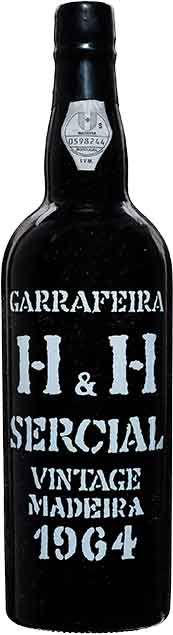

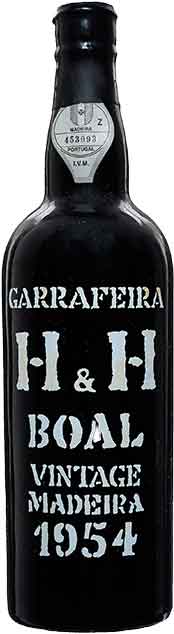

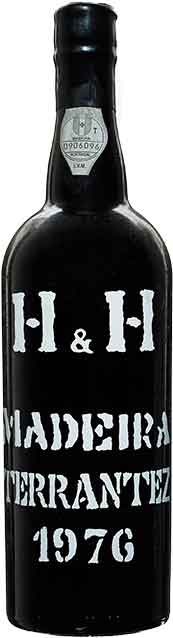

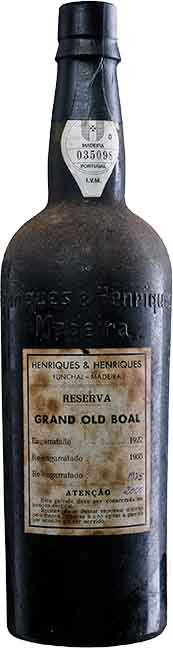

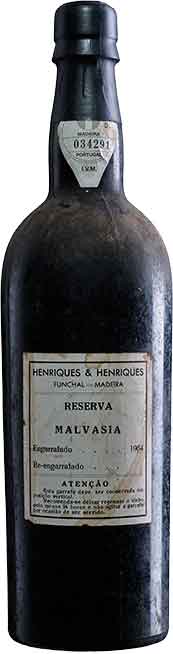

Henriques & Henriques

Portugal ➜ Madeira DOC 19.0-20.0% ABV